Fossilized teeth discovered during a long-term archaeological excavation in northeastern Ethiopia suggest that two distinct hominin species inhabited the same region between 2.6 and 2.8 million years ago. Notably, one of these species may represent a previously unidentified branch of human ancestry.

This remarkable find sheds light on the intricate narrative of human evolution. Among the ten teeth unearthed between 2018 and 2020, a subset belongs to the genus Australopithecus, a significant early human relative. In contrast, three teeth retrieved in 2015 correlate with the genus Homo, which includes modern humans (Homo sapiens). These findings were published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The occurrence of two hominins coexisting within the fossil record is uncommon and has previously led researchers to assume that Homo emerged after Australopithecus. Australopithecus species were bipedal, similar to modern humans, but had smaller brains akin to those of apes. Conversely, the emergence of Homo species, characterized by larger brains, is often interpreted as an evolutionary advancement toward modern humans.

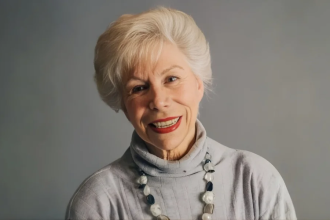

However, this new evidence illustrates that hominins thrived in various forms simultaneously. “This new research shows that the image many of us have in our minds of an ape to a Neanderthal to a modern human is not correct — evolution doesn’t work like that,” noted study coauthor Kaye Reed, a research scientist and professor emerita at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University. “Here we have two hominin species that are together. And human evolution is not linear; it’s a bushy tree, there are life forms that go extinct.”

Since 2002, Reed has co-led the Ledi-Geraru Research Project, which seeks to uncover evidence of early Homo species. The project previously identified the oldest known Homo jawbone, dated at 2.8 million years. It is also investigating later traces of Australopithecus afarensis, the species famously represented by the fossil Lucy, which was discovered in Ethiopia in 1974.

The current excavation yielded Australopithecus teeth which were compared to known species, including afarensis and another hominin group, garhi, but did not match. Researchers believe these teeth belong to a novel Australopithecus species that lived alongside early Homo.

“Once we found Homo, I thought that was all we would find, and then one day on survey, we found the Australopithecus teeth,” Reed stated. “What is most important, is that it shows again that human evolution is not linear.” The teeth labeled LD 750 and LD 760 are linked to the new Australopithecus species, while LD 302-23 and AS 100 are from the early Homo species.

The teeth were recovered from the Afar region, known for its rich fossil record and early stone tools. This area experiences tectonic activity, exposing ancient sediment layers that reveal nearly five million years of evolutionary history.

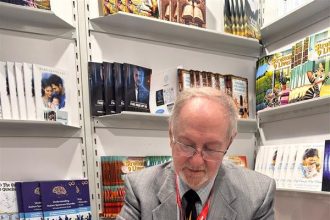

“The continent is quite literally unzipping there, which creates a lot of volcanism and tectonics,” explained Christopher Campisano, study coauthor and associate professor at the Institute of Human Origins. The Australopithecus teeth are dated at approximately 2.63 million years, while the Homo teeth are dated between 2.59 and 2.78 million years.

As the team gathers more data, they remain cautious in classifying species associated with the teeth, emphasizing the need for additional fossils to differentiate between Australopithecus and Homo.

The discovered Australopithecus teeth have characteristics resembling those of afarensis but feature unique traits not previously identified in this or the garhi species. “Obviously these are only teeth,” Villmoare noted. “But we are continuing fieldwork in the hopes of recovering other parts of the anatomy that might increase resolution on the taxonomy.”

Finding the teeth was a complex endeavor, Campisano added. “You’re looking at little teeth, quite literally, individual teeth that look just like a lot of other little pebbles spread on the landscape,” he explained. The excavation team relies on local experts to identify these fragile artifacts amid the terrain.

This study provides valuable insight into a pivotal era of human evolution, according to Dr. Stephanie Melillo, a paleoanthropologist who has worked on related research projects in Ethiopia. The period between three and two million years ago remains elusive due to the limited sediment deposition in the region, which restricts the fossil record.

The authors’ findings indicate that another species coexisted with Homo in the Afar region, likely an Australopithecus, as opposed to the previously suggested Paranthropus.

When Australopithecus and Homo occupied the Afar Region, the climate was starkly different from today, characterized by a dry season punctuated by brief wet periods. Researchers are now investigating whether the two hominins had overlapping diets, which could reveal insights into their interactions and competition for food.

As future discoveries unfold, Reed expressed hope that they will clarify the coexistence of these ancient ancestors. “Whenever you have an exciting discovery, if you’re a paleontologist, you always know that you need more information. More fossils will help us tell the story of what happened to our ancestors a long time ago,” Reed concluded.