A rare snowfall in the Atacama Desert, the driest region on the planet, has brought operations of one of the world’s leading telescope arrays to a standstill, raising concerns about the impact of climate change on future extreme weather events.

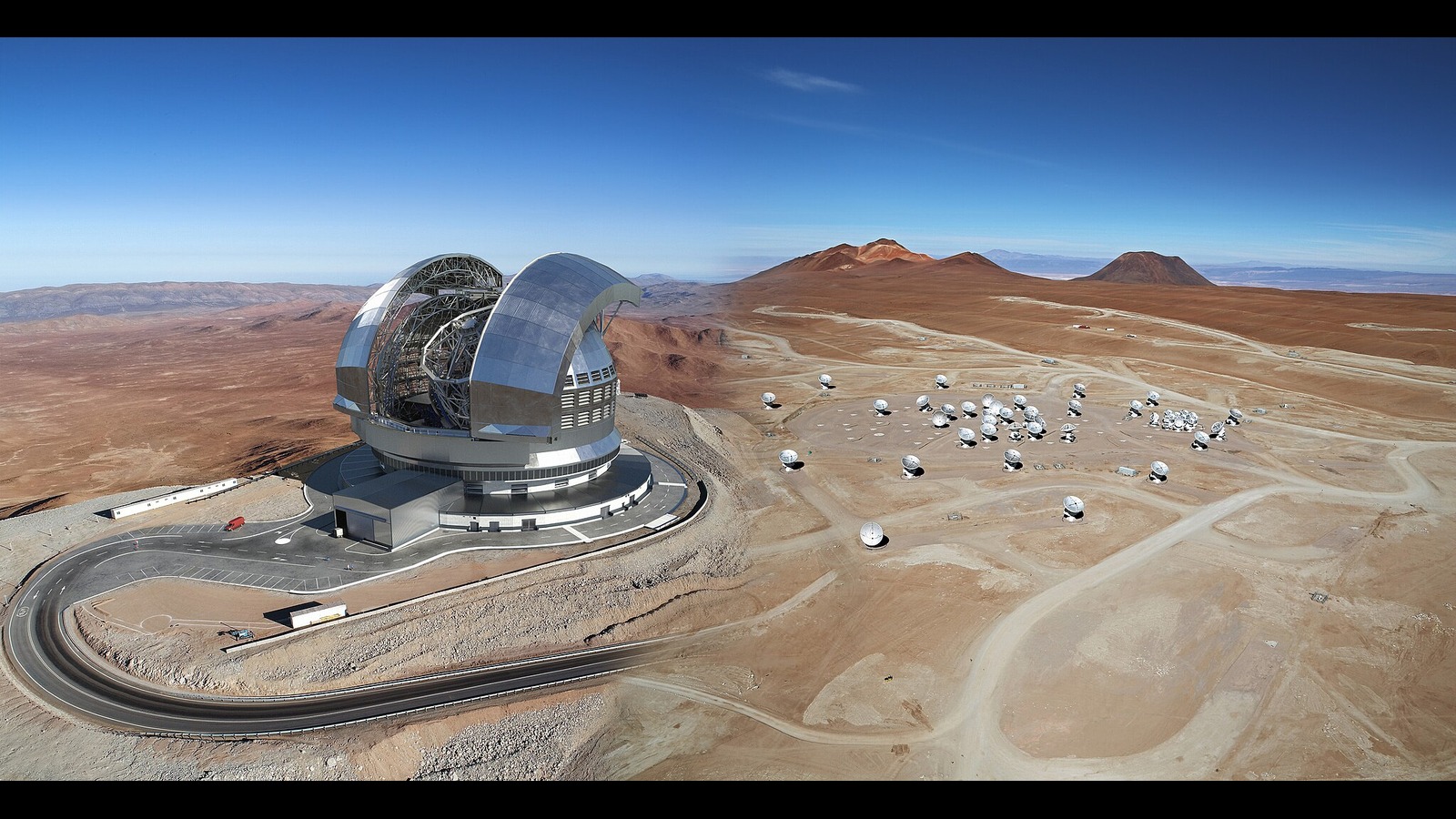

The snow has coated parts of the Atacama Desert, which typically receives less than an inch of rainfall annually, affecting the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an extensive network of radio telescopes situated in northern Chile. The snowfall impacted ALMA’s Operations Support Facility, located at an elevation of 9,500 feet (2,900 meters) and approximately 1,050 miles (1,700 kilometers) north of Santiago. Operations had to be halted since Thursday, June 26.

“There hasn’t been a record of snowfall at the base camp for over 10 years. It doesn’t snow every day at ALMA!” representatives of ALMA noted in a message to Live Science via WhatsApp.

ALMA’s radio telescope array is situated on the Chajnantor Plateau, a desert plain at 16,800 feet (5,104 meters) in the Antofagasta region of Chile. Typically, this high plateau experiences about three snowfalls each year. According to Raúl Cordero, a climatologist at the University of Santiago, these snowstorms generally occur during two seasons: February’s “Altiplanic Winter,” resulting from moist air masses from the Amazon, and again from June to July during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter.

“In winter, some storms are fueled by moisture from the Pacific, which can extend precipitation to the Atacama Desert’s coastal areas,” Cordero explained. At elevations above 16,400 feet (5,000 meters), annual snowfall ranges from 8 to 31 inches (20 to 80 centimeters). However, at ALMA’s base camp located at 3,000 meters (9,840 feet), “snowfall is much less frequent,” Cordero added.

The recent snowfall was caused by unusual atmospheric instability over northern Chile. The Chilean Meteorological Directorate had issued alerts for snow and strong winds due to the passage of a “cold core” through the region, according to meteorologist Elio Brufort. “We issued a wind alert for the Antofagasta region and areas further north, with gusts reaching 80 to 100 km/h [50-62 mph],” Brufort told local media.

Accompanying the snow were heavy rains further north, which led to swollen streams that damaged several properties. School closures were mandated, and reports of power outages and landslides emerged, though no casualties have been recorded. This snowfall event has not been witnessed in nearly a decade.

As conditions remained severe on the Chajnantor Plateau, ALMA announced that scientific operations would continue to be suspended to protect the antennas from the harsh weather. Early Thursday, the observatory initiated its “survival mode” safety protocol: temperatures dropped to 10 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 12 degrees Celsius) with wind chills reaching minus 18 F (minus 28 C), creating challenging working conditions in the high-altitude environment.

During this protocol, ALMA’s large antennas were realigned to face downwind, minimizing potential damage from snow accumulation and strong gusts.

“Once the storm passes, snow-clearing teams are immediately activated to visually inspect each antenna before resuming observations,” ALMA representatives stated. “This has to happen quickly, as some of the best observing conditions occur just after a snowfall: the cold helps lower air humidity, which is the main interference with our measurements.”

ALMA, comprising 66 high-precision antennas spread across the Chajnantor Plateau, is recognized as the most powerful radio telescope globally, designed to endure extreme weather conditions. The interruption of operations due to snowfall raises critical questions regarding the array’s functionality as the climate continues to warm.

Typically, the Atacama Desert receives only 0.04 to 0.6 inch (1 to 15 millimeters) of precipitation annually, with many areas lacking measurable rain or snow for years at a time. Could incidents like this become more common? “That’s a good question,” Cordero replied.

While it remains premature to conclusively associate lower-altitude snowfall in the desert with climate change, Cordero noted that “climate models predict a potential increase in precipitation, even in this hyper-arid region.” He concluded, “We still can’t say with certainty whether that increase is already underway.”